When it comes to addressing the economic crisis created by the coronavirus pandemic how we spend the vast sums of public money being generated could forever alter the fossil fuel era.

But all is not equal when it comes to marshaling resources to fight the crisis. Indeed, the world is increasingly being sorted into two camps — those who can print money and those who can not. While we struggle to generate attention to the climate impacts of the historic decisions being made in the rich world, the rest of the world is quietly sinking into an economic abyss with dramatic ramifications for climate change and beyond. As the world lurches down that dark path one institution with a progressive approach to climate change looms large — the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

A Two Tiered World: Print Money, Or Rely On The IMF

In the developed world emergency relief packages have been passed that range from $800 billion in Germany to a historic $2 trillion in the US to a truly staggering $7 trillion in China. While enormous, those sums are just the beginning, with Japan eyeing another $1 trillion and the United States hard at work on another round of measures as we speak. The rich world has spared no expense as it revved up an engine of public finance to fight off a looming economic depression. The rest of the world is not so lucky.

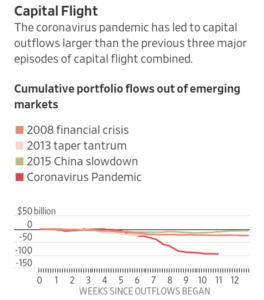

Take India whose initial stimulus response measures added up to all of $23 billion — roughly 2% of the US response. That in a country whose GDP had already fallen to its lowest point in 6 years before COVID hit. But it’s not just the fiscal fire power that’s lacking, these countries also face a similar nemesis — capital flight.

Source: WSJ

As the crisis has unfolded emerging markets have woken up to the giant sucking sound of global financial institutions withdrawing over $96 billion in stocks and bonds as they retreat to safe havens to ride out the crisis. This has set up a situation in which vulnerable countries may be forced to consider defaulting on loan obligations. If they do, it could trigger a potential wave of sovereign defaults and the need for bailouts reminiscent of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

But unlike rich countries whose currencies are highly valued, economies are strong, and investor appetite high, poor countries have few options. Turning on the printing press risks disastrous runaway inflation. These countries have few places to turn except the Bretton Woods system and the IMF.

IMF as emerging market lender of last resort

That lack of options is precisely why the IMF reports that over 90 countries have requested assistance which could total over $2.5 trillion. While it pales in comparison with the need, let alone the sums being announced in the rich world, the IMF has readied $1 trillion to support emerging markets in response. It’s also eyeing new innovative facilities to support stronger emerging market economies facing a cash crunch driven by an exodus of US dollars. All told, the IMF managing director Kristalina Georgieva has been outspoken about the fact that they ‘stand ready’ to deploy their resources.

That gives the IMF the opportunity to demonstrate sorely needed leadership which could revive the importance of the institution. That’s important because long before the crisis, Western-backed international financial institutions like the World Bank and the IMF had entered an age of crisis of their own. With new Asian backed multilateral development banks like the AIIB as well as bilateral aid institutions challenging their historical power over development finance, many were asking what their role should be in the 21st century. But with a new great depression looming and emerging markets in dire need of financial aid the IMF now looks to be more important than ever.

IFI’s Are The New Climate Leaders

But what exactly does any of this have to do with climate change? As it turns out many of these international financial institutions, including the IMF, have at times been at the forefront of climate action and energy transition over the past decade. The World Bank, for instance, (where Georgieva worked prior to the IMF) was the first financial institution in the world to enact restrictions on coal finance. Since that time 126 global institutions have followed suit.

But the World Bank and its fellow IFIs didn’t stop at coal. They’ve increasingly led the world in clamping down on fossil fuel finance across the board. Not long ago the World Bank became the first international financial institution (IFI) to enact restrictions on upstream oil and gas while the European Investment Bank’s new policy amounts to a near blanket ban on all fossil fuel finance. These moves even impacted China whose own IFI, the AIIB, recently enacted coal restrictions of their own. All told, these once reviled institutions are for all intents and purposes progressive climate institutions.

The IMF is no different. Prior to the crisis Georgieva had made addressing climate change a top tier priority for the institution. That included making climate change central in country analysis and stress testing undertaken by the institution, a decision that could prove fateful for the IMF’s new role as lender of last resort for everyone not running a printing press of their own.

A New Era For Climate Finance: First Comes Debt, Next Comes Debt Relief For Climate Outcomes

The IMF’s role could be all the more significant because it is no stranger to conditionality. Indeed, it’s not exactly revered for its checkered past of tying emerging market bailouts to painful reforms that have come at the expense of poor citizens around the world. But this time can be different and Georgieva could change the trajectory of the fossil fuel era if she is up to the task. Because she now has a unique opportunity to set a new vision for what the institution expects as it deploys its resources — a vision that can accelerate the retirement of old, polluting and uneconomic fossil fuel assets to help free up scarce public resources that can be reinvested in the industries and jobs of the future.

Take coal plants for instance. There are surprisingly large numbers of old polluting coal plants in some emerging markets, and many more new uneconomic units being planned. Carbon Tracker estimates for instance that 42% of the world’s coal fleet operates at a loss. Most of those uneconomic units are in the rich world today. But fast forward to 2030 (just a decade away) and that number rises to nearly 90% encompassing many emerging markets. Indeed, key coal countries like Turkey, South Africa, and Indonesia will all face coal fleets more expensive to run than building newer, cheaper cleaner energy.

But absent a systemic shock those plants will keep operating under a zombie-like inertia. Which is why this moment and the interventions made by the IMF are so important. A shock like this serves as an opportunity to let developing countries get out from under these aging assets and free up scarce public dollars. Even before the crisis South Africa had awoken to this opportunity and was exploring an $11 billion deal with a club of international donors that would pave the way for new clean energy by waiving old debt in exchange for coal closures. Now the IMF should go further.

The IMF could, for instance, consider a new debt relief facility or general lending policy tied explicitly to the closure (not sale) of old polluting coal assets. This would enable countries with sizable coal fleets like South Africa or coal exports facilities like Indonesia to chart a new course with the help of international finance. Similarly, they could condition debt relief to countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Philippines, or Vietnam on not building new coal plants. A more recent analysis by Carbon Tracker found that it is already cheaper to build new solar and wind power than to build new coal power in all major markets around the world which makes those conditions just…logical.

Such policies would usher in a new era of ‘climate finance’ that would define interventions in terms not just of their ability to accelerate clean energy, but of their ability to retire old uneconomic fossil fuels. On a cost per ton basis the latter generates far more bang for the buck. Already leading economists like Joseph Stieglitz are calling for debt relief for poor countries to combat the Covid crisis — now is the time for innovative new policies that tackle the climate crisis at the same time.

Ultimately, the fate of the energy transition and climate change for millions in emerging markets hangs in the balance. The IMF and other IFIs like the World Bank need a new vision for their role in the 21st century. They’ve taken important steps to make addressing climate change central to that role. Stepping up now would cement that vision for the new world we’ll enter post Covid-19 crisis. Few may be watching now, but when all is said and done the world very well may wake up to a cleaner, more resilient world made possible by Kristalina Georgieva and the IMF.